The Power of Physical Activity: the Human Capital approach

Richard Bailey, PhD FRSA, International Council of Sport Science and Physical Education, Berlin

As the conclusions of the Physical Activity Serving Society (PASS) project led by the Sport and Citizenship Think Tank with the support of the ICSSPE have emphasized, a transversal promotion of physical activity is necessary in our societies, because the benefits are many and varied for our Human Capital.

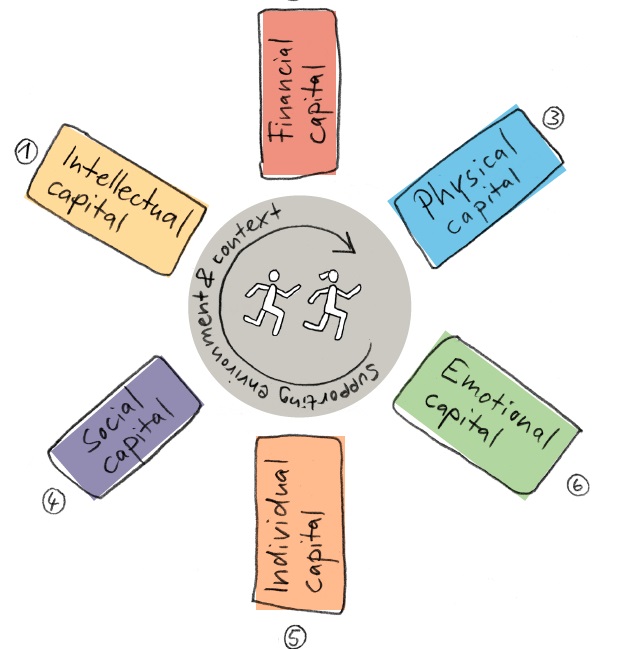

Figure 1: The Human Capitals

The last decade has been an important one for those working in physical activity. Scientific advances mean that we now know a great deal about the importance of active lifestyles. We are starting to understand, for example, how exercising of the body affects the functioning of the brain, how playing games in groups can help teach children skills that are carried over into their everyday life, and how regular activity can start a cascade of benefits that affects almost every aspect of life.

And yet there is widescale concern about the state of physical activity around the world. Most people are not active enough to take advantage of the potential benefits, and the origins of the problem can be traced to childhood. A recent analysis found the first signs of a decline in activity levels in children as young as 6 years old. So, it is not surprising that a review of data from 105 countries found that four-fifths of adolescents did not reach recommended levels of activity. Young people in Europe spend more time after school in sedentary pursuits than play, and fewer are commuting to school by foot or bicycle. These findings have serious health consequences as lack of activity is one of the main risk factors of non-communicable diseases worldwide – heart disease, stroke, diabetes and cancers – which are currently the leading causes of death worldwide.

Inactivity is fast-becoming the new norm, and we are paying the price for it with deteriorating quality and quantity of life. As a consequence of this predicament, the promotion of physical activity is widely regarded as a global health priority, and the failure of large numbers of people to achieve even minimal levels of activity could justifiably be judged a health crisis. Almost every country has a physical activity strategy, and a diverse group of agencies are joining governments and non-government organisations to meet the challenge of an inactivity pandemic. Among the most visible of these new players come from the Sport Business.

The development of Designed to Move, led by Nike, and supported by the ICSSPE and the American College of Sports Medicine, has attracted a great deal of attention. Associated programmes focusing on “Active Schools”, “Active Cities”, and so on, have sought to capitalise on its success in grabbing the attention of policy makers and practitioners. These initiatives have introduced a marketing perspective to the promotion of physical activity by articulating simple and clear messages, recognising that people make decisions with both their reason and emotions, and using research to strengthen and guide the agenda. In other words, they have started to teach those of us working in public health, sport and education how to sell our product – physical activity.

The Human Capital Model is one of the best-known offspring of the Designed to Move initiative (see Figure 1). The basic idea is that the stock of competencies, knowledge and personal attributes are embodied in the ability to take part in physical activities, and that these activities produce values that are realized through increased well-being, educational achievement and, ultimately, economic value.

The HCM conceptualizes development in terms of different forms of ‘Capital’, as follows:

- Physical Capital: The direct benefits to physical health and positive influences on healthy behaviours.

- Emotional Capital: The psychological and mental health benefits.

- Individual Capital: The elements of a person’s character – e.g., life skills, interpersonal skills, values.

- Social Capital: The outcomes that arise when networks between people, groups, organizations, and civil society are strengthened.

- Intellectual Capital: Cognitive and educational gains.

- Financial Capital: Gains in terms of earning power, job performance, and productivity, alongside reduced costs of health care and absenteeism.

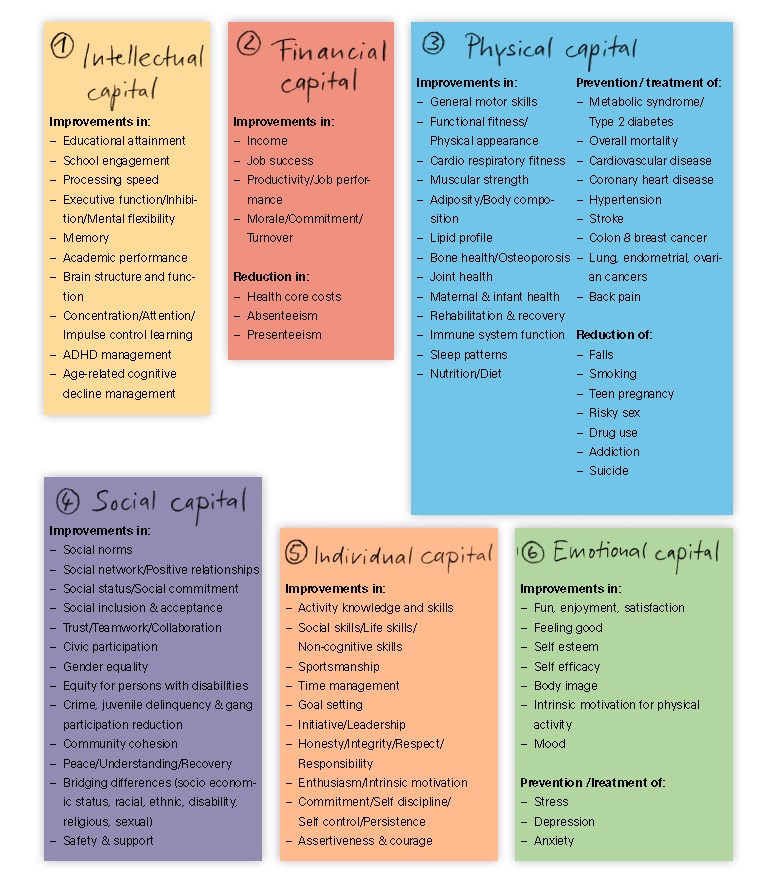

The different Capitals represent different types of outcomes associated with physical activity, and each of these outcomes was evaluated for the amount, strength and consistency of the evidence in its favour. The result was the identification of distinct benefits that were supported by the peer review process, each organised into one of the six general Capitals (see Figure 2).

Figure 2: Identified benefits of physical activity

Different readers are likely to be more interested in some Capitals than others. Generally speaking, however, one theme seems to garner the most attention – Intellectual Capital – reflecting the interest that almost all of us have in the education of children and young people. In this area, it seems that the Ancient Roman poet Juvenal’s maxim was right: Mens sana in corpore sano (‘a sound mind in a healthy body’). Numerous studies have been carried out in recent years on the association between physical activity and cognitive functioning, and findings are encouraging. Children, in particular, benefit improvements in their physical fitness and levels of activity. A recent report to the OECD, based on a systematic review of the evidence, stated that the case for significantly increasing the amount of physical activity in children’s lives was unarguable, and there seems to be no downside to doing so. In fact, increasing the amount of activity at school had the potential to have a big impact of student learning:

- More positive attitudes to school and teachers;

- Greater motivation in lessons;

- Higher scores of tests and examinations, especially in mathematics;

- Improved memory, concentration and mood; and

- Reduced incidence of unhealthy behaviours.

To this list we can add findings linked to the other Capitals, such as those showing improved social and life skills, enhanced self-esteem, and reduced stress, which gives us reason to be confident that active children – and active people – tend to better than those who live sedentary lives.

MEMBERSHIP

MEMBERSHIP CONTACT

CONTACT FACEBOOK

FACEBOOK