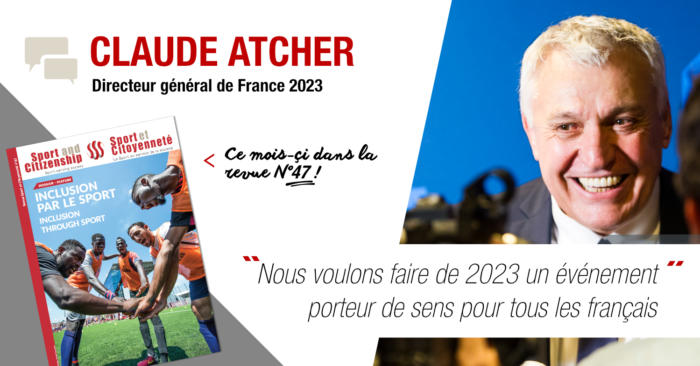

“France 2023 must resonate with all French people”

In 4 years, France will be hosting the Rugby World Cup, following a bid which was strongly focused on the social aspect. Claude Atcher, Director general of France 2023, explains this vision and the steps already taken to reinforce the event’s social impact.

You have stressed your ambition to make the France 2023 project meaningful several times. Why is it important?

CA: In 2007 I was already in charge of organising the Rugby World Cup in France. One of the major differences between then and the present edition, as I see it, is the social acceptability aspect. In 2007, we concentrated on the organisation, the marketing aspect and ticket sales, without ever questioning its usefulness. That is no longer the case. Nowadays, as soon as you take responsibility for organising a major sporting event, it has to be acceptable and accepted by the whole population. In order to achieve this, it must be exemplary. The social, environmental and financial aspects are all linked. To be exemplary, you need a strategy. We will be sharing ours in the coming days, by publishing a manifesto on our vision and ambitions for 2023.

The basic objective is simple: to be involved in society and make this event a driving force for tomorrow’s society. We don’t have any pretensions about changing society, but we want to be able to say that, temporally and territorially, we play a part in the lives of French people. From that starting point, we want to (re)create a social link and touch different regions. We will ensure that our project is accessible to all, without discrimination, with respect for other people. We want to run a unique, different and meaningful event. The specificity of the Rugby World Cup is that it stages matches in 10 different cities. For a month and a half, the teams will be accommodated in base camps in 53 other towns. This is an event that will affect everyone. If we want it to be accepted by everyone, we need to make sure that it is useful and that the whole of France can join in the fun, because rugby is not a sad sport.

“An event that is acceptable and accepted”

How do you intend to achieve this?

CA: By putting our commitment into practice. For example, we are working with the Ministry of Education on mobilising 15,000 young people, so that they learn to sing the anthems of all the participating teams. In rugby that is always a special, very emotional moment, with the pride of representing a country. The idea is not that they will just learn the anthems, but they will find out about the geography, history, culture, music and economy of each country. That way, young people will be fully involved in the context of the country when they go on to the pitch with the players.

We have also created an endowment fund, “Rugby au Coeur”, for financing and supporting social and environmental projects and associations. With the Federation’s decentralised organs, we have set up Local Coordination Committees to bring together the sporting, economic and political stakeholders in each region and to follow up the launch and evaluation of social and educational action supported by the endowment fund and/or by local authorities and private partners. We are also working with the Ministry of Employment to make 2,023 apprentices available to clubs to produce an overview of current practice and get ready to welcome new players and people. These examples are part of our impact and legacy commitments. In any case, since France 2023 has a public interest status, all the profits raised will be redistributed in schemes for development.

In June you ran a consultation process on the World Cup’s social impact, in partnership with our Think Tank. Why are such meetings useful and what did you learn from these discussions?

CA: It was a very unusual approach. We are one of the first sporting events to do this. We didn’t want to waste time in consulting financial, political and sporting stakeholders in order to identify their expectations. With Sport and Citizenship we ran four tests in four different regions (Lille, Marseille, Toulouse and Nantes). These discussions enabled us to move on to the next stage: how to develop useful, meaningful activities, in line with the particular needs and expectations of each region?

“Measure the impact of our actions”

Rugby is a popular sport, but its image has suffered a bit in the last few years. How can Rugby 2023 contribute to developing rugby in all its forms?

CA: The first challenge is to restore the image and show the virtues of this sport. Rugby was born 200 years ago when William Webb Ellis picked up the ball and ran with it during a school football match. From the start, this initiative gave the sport a meaning which has since been confirmed at various events (such as, for example, the World Cup in South Africa when Nelson Mandela came into the stadium wearing the Springbok shirt and cap). With the advent of professionalism, sport as a spectacle, and more money, rugby lost touch with its original virtues. The World Cup aims to give back to this sport the place it deserves in society, to reach new members of the public and attract new players. French rugby has a stronger following among older age groups. This is one big challenge. Another is to recreate the link between players and supporters, which is missing today. The World Cup is also the opportunity to show that rugby is not a dangerous sport, contrary to the image it sometimes has. We need to emphasise the educational virtues of rugby and give them meaning in concrete projects.

MEMBERSHIP

MEMBERSHIP CONTACT

CONTACT FACEBOOK

FACEBOOK